13 minutes

Mutual TLS and Load Balancers

This blog on Mutual TLS (a.k.a. Client Certificate Authentication) was originally written for some work I was doing at the time. It discusses Mutual TLS and the issues that are encountered when trying to use it with load balancers. It is written from the perspective of using Mutual TLS for our usecase (ensuring that a server only allows requests from known/approved clients).

In this discussion, diagrams will reference TLSv1.2 only, although many sources will reference both TLSv1.2 and TLSv1.3.

Background Knowledge

Authentication vs Authorisation

Authentication is verifying you are who you say you are (e.g. “I am an admin”).

Authorisation is verifying you are permitted to do what you’re trying to do (e.g. “I want to delete this user”).

We are interested in authentication in this blog as we are trying to prove to the server that we are who we say we are.

What is a certificate?

A certificate is a document used to prove the ownership of a public key. It contains some information about the certificate holder (a server certificate contains the hostname of the server, a client certificate contains an email address or personal name) and it contains the public key itself.

A certificate is signed by a trusted certificate authority, which states that the contained public key does belong to the provided hostname (or email/name).

Certificates are used as a part of public-key cryptography where public and private keys are generated as key pairs in such a way that lets the public key encrypt, but not decrypt messages and lets the private key decrypt, but not encrypt messages. This way, someone can encrypt messages using a public key, and no one but the holder of the corresponding private key can decrypt those messages, allowing for secure communication over the internet.

What is TLS?

TLS stands for Transport Layer Security, and whilst the name would indicate that it sits in the Transport Layer (layer #4 of the OSI model), it doesn’t neatly fit on any of the OSI layers. All we need to know for this discussion is that TLS happens before HTTP does (layer #7, the application layer). This will be important later.

TLS is a protocol for securing communication over a network (often the internet) via encryption. It is what provides the ‘S’ (‘Secure’) in ‘HTTPS’. The high level overview for how it works is:

- Client initiates connection

- Server authenticates itself using a certificate

- Client verifies server authenticity

- Encryption is set up

- Normal, encrypted, communication happens

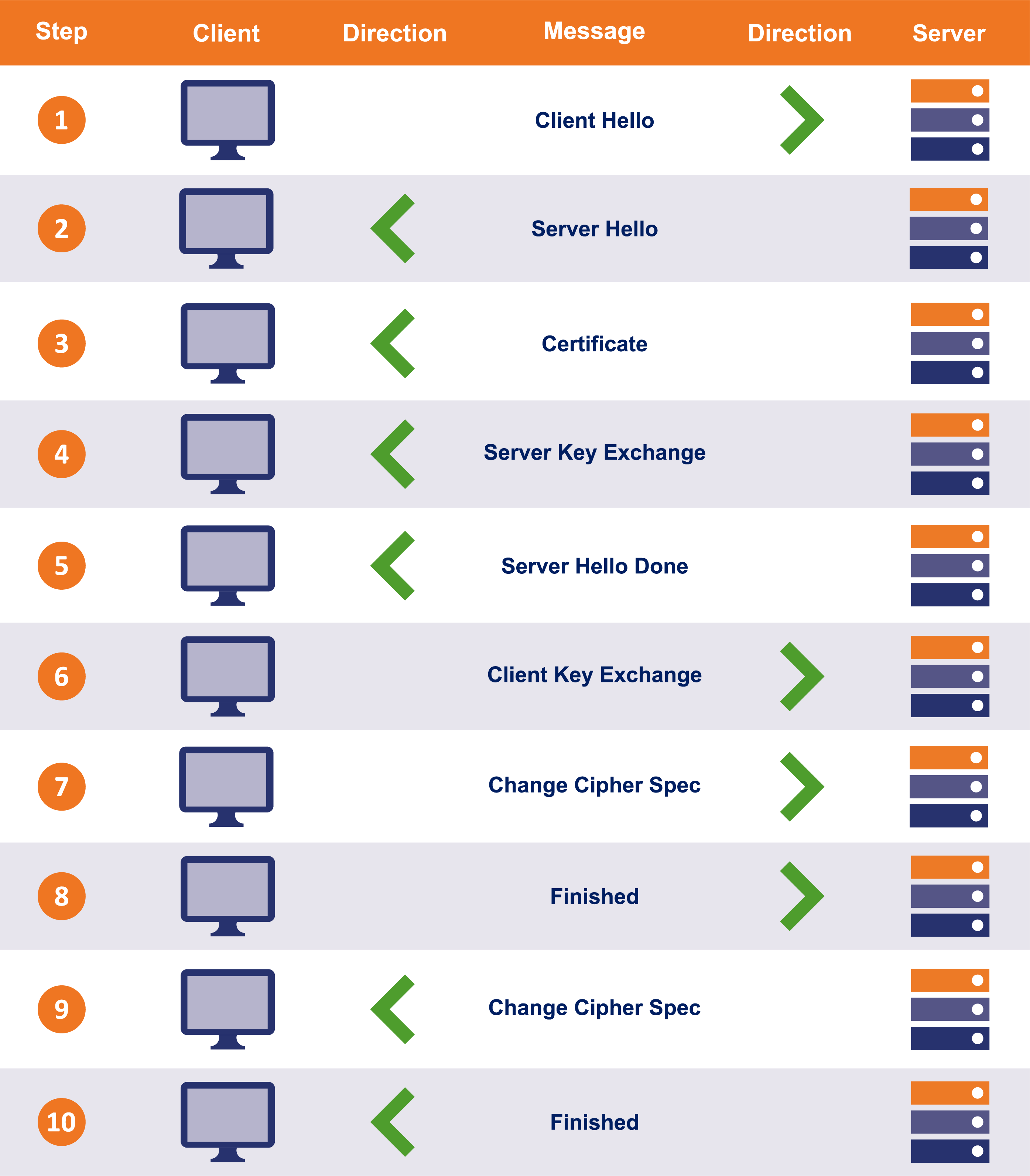

Steps 1-4 are called the TLS handshake, and this diagram shows each step of the handshake process in detail:

(Source: thesslstore.com)

(Source: thesslstore.com)

The important part of this handshake for us is step #3 in this diagram, where the server authenticates itself by providing its certificate. Behind the scenes the client will verify it trusts this certificate by checking the server’s certificate is signed by a trusted certificate authority and ensuring that the server has the corresponding private key (how does private key verifcation happen?). The main takeaway from this section is that in normal TLS, only the server has authenticated itself, the client is anonymous, it could be anyone.

What is Mutual TLS?

Mutual TLS (mTLS) is where both the client and the server authenticate themselves and verify their identities. Mutual TLS is achieved by normal TLS and something called Client Certificate Authentication (CCA) (v1.2, v1.3) — where the client provides a certificate to authenticate themselves. One thing to note is that mTLS is a part of the TLS specification, it is not added on top.

The Handshake

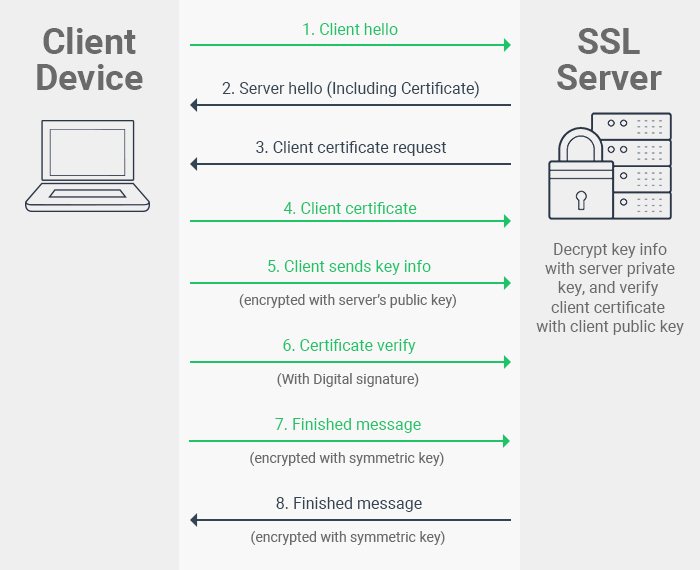

CCA is performed during a TLS handshake like so:

(Source: comodosslstore.com) This diagram shows a slightly simplified TLS handshake, to focus on the CCA part of the process.

(Source: comodosslstore.com) This diagram shows a slightly simplified TLS handshake, to focus on the CCA part of the process.

After the initial server response messages, the server sends a Certificate Request message (v1.2/v1.3), indicating that the server wants to verify the identity of the client.

The client then responds with a Client Certificate message (v1.2, or Certificate in v1.3) which contains the client’s certificate. The server verifies this certificate is signed by a trusted certificate authority, in the same way the client did for the server’s certificate.

This is followed by a Certificate Verify message from the client. This verifies to the server that the client has the private key corresponding to the certificate they provided.

Common Mutual TLS Usage

A common use case for mTLS, and the one we care about, is where the server wants to only allow approved clients to make requests of it.

To achieve this, there must be some information exchanged between the client and the server as a one-time set up. Typically, this information consists of the client’s company sending a Certificate Signing Request (CSR) to the server’s company, and receiving the certificate they will use during mTLS in return. In this case, the server’s company is acting as a certificate authority and the client’s company is acting as the applicant.

To create a CSR:

- The applicant generates a public-private key pair

- The applicant bundles their public key with some information identifying the applicant (such as organisation name, email, location, etc)

Once the server (certificate authority) receives the CSR, they sign it using their own private key, creating a certificate. This certificate is sent to the client (applicant).

This signed certificate will be the client’s certificate during the mTLS handshake.

As mentioned in the handshake section, the client must also prove they have the corresponding private key. This is because the certificate should be able to be public (the certificate is not private/hidden information), and as such, only providing a certificate is not proof of identity. One must provide both the certificate and prove that they have the private key corresponding to that certificate.

This way, the server ‘approves’ clients by signing their CSRs and giving them certificates signed by the server. The server can then verify that is it an approved client as the certificate provided by the client will be signed by the server’s own private key. This is done by adding the certificate authority (the server itself in this case) to the list of trusted authorities on the server.

Note: You could allow certificates signed by any certificate authority, not just the server itself, this is just the use case I have seen most commonly in my research.

Mutual TLS Limitations

Headers

Since the TLS handshake occurs below/before where HTTP(S) does, headers cannot be used as a part of mTLS. This means that, without a workaround, mTLS cannot be optional or done on a case-by-case basis, it must either be required or not required for a domain, there is no middle ground.

Load Balancers

An issue also arises when trying to use load balancers (or other proxies). Since they often terminate incoming request connections and create new ones to applications (huh?), the application server could not check if a client certificate is an ‘approved’ certificate.

This gives two options when using load balancers:

- Make the load balancer handle all the authentication itself

- Make the load balancer pass the certificate information to the application for verification

The first option is effort-intensive, and might not be feasible for all use cases. It also is not an option on many common load balancers provided by cloud platforms.

The second option is the more common one. The load balancer will use default mTLS verification with an incoming connection (that is, verify that the client has the private key corresponding to the certificate & public key provided). Then, in the new (non mTLS) connection to the application, add the certificate to a header so that the application can verify the certificate is ‘approved’. To be clear: the load balancer will not usually be checking the certificate is from a trusted authority, only that the client has the private and public keys.

The extra required certificate validation will then be carried out by the application. Usually this will include checking that client certificates are the expected certificates (they are from ‘approved’ clients). This is also why HTTP (not HTTPS) responses are more common when doing mTLS these days (as opposed to TLS handshake failed messages), as the initial connection to the load balancer succeeds, but then the application denies the request via an HTTP status code, which is (usually) passed through the load balancer to the client.

Notes About Mutual TLS in .NET

-

In .NET (both Framework and Core), 403 Forbidden status codes are returned by authentication handlers instead of 401 Unauthorized as you might expect. This is because if the client certificate is invalid, the application should never be reached (since TLS happens during connection setup, below the application layer). From the Microsoft documentation:

If authentication fails, this handler returns a 403 (Forbidden) response rather a 401 (Unauthorized), as you might expect. The reasoning is that the authentication should happen during the initial TLS connection. By the time it reaches the handler, it's too late. There's no way to upgrade the connection from an anonymous connection to one with a certificate. -

There are a couple of Microsoft-provided workaround examples to enable optional client certificates, here and here.

-

In Azure the header added by load balancers which has the client certificate is the

X-ARR-ClientCertheader (source). -

.NET authentication handlers can be configured to use external proxy/load balancer headers and check authentication against them. See the documentation.

An Issue We Found

We were setting up mTLS to enable us to securely send data to a partner’s server without requiring other forms of Authentication. It turns out that this partner did not implement mTLS on their server correctly, they instead effectively implemented normal TLS (anonymous TLS). This means than any client (not just us) could make requests to the server.

What Was Happening

The partner asked us to include the certificate in a X-ARR-ClientCert header from the beginning of the request. This is an immediate orange flag as these kind of headers are usually only used by load balancers (or other proxies) that sit in front of application servers, there are some potential use cases though, so not an outright problem. This did encourage me to investigate further though.

It appears that the server was checking these two things, independent of one another:

- The client is providing a certificate, and the client has the corresponding private key to that certificate. It does not matter which certificate authority has signed this certificate.

- The

X-ARR-ClientCertheader contains the expected certificate.

What this means is that a client can provide any certificate they want (as long as they have the corresponding private key) and an ‘approved’ certificate as a header (which is treated as public information), and the server will allow their requests.

My Conclusions

My initial thought was that the server must have a (assumedly Azure) load balancer sitting infront of it (and this might’ve been the case, I had no way to know), but a couple of things made me think that’s not true:

- I would assume a good load balancer would strip these headers and re-add them itself to prevent this exact situation

- In all my testing I never had a TLS handshake failure, but always an HTTP response code, this indicated that whatever the requests are hitting do not have ‘proper’ mTLS enabled (I am unsure if this would be normal under normal load balancer-mTLS functionality)

- I found no evidence of CCA during TLS handshakes (using Wireshark)

The server was definitely attempting some form of mTLS, otherwise connections without client certificates in the header available would not have failed (they did fail, which is better than nothing), but I cannot pinpoint exactly what was wrong from a purely outside viewpoint.

I have glossed over many details, and many technicalities, but ‘proper’ mTLS is very feasibly possible, and thinking we’re protected by it when we are not is more dangerous than just not being protected by it.

Technical Testing

Wireshark

I initially attempted to use Wireshark to investigate whether or not the server was using mTLS. To do this I made requests to the server’s endpoint with Wireshark open and used the following filters:

tls.handshake.certificate and tls.handshake.type == 16— this looks for TLSCertificatemessages (can be either client or server) andClientKeyExchangemessages (handshake type 16), together these indicate a client responding to a certificate request from a server.tls.handshake.type == 13— this looks for TLSCertificateRequestmessages, which can be used to find servers requesting certificates from clients.

Neither of these filters bore any results on connections to the server and as such I concluded that the server was not using ‘proper’ mTLS. This did not rule out the server doing mTLS at an application layer level, or potentially using some kind of optional mTLS, so further investigation was required.

I do think that my conclusions from Wireshark are a bit suspect, due to the fact that the server always returns an error if a client certificate was not set up in Postman. Meaning that somewhere, something is asking for our client certificate.

Postman

I had already tried making requests to the server with no client certificate enabled, whilst sending either the legitimate or illegitimate certificate in the X-ARR-ClientCert header, with no success.

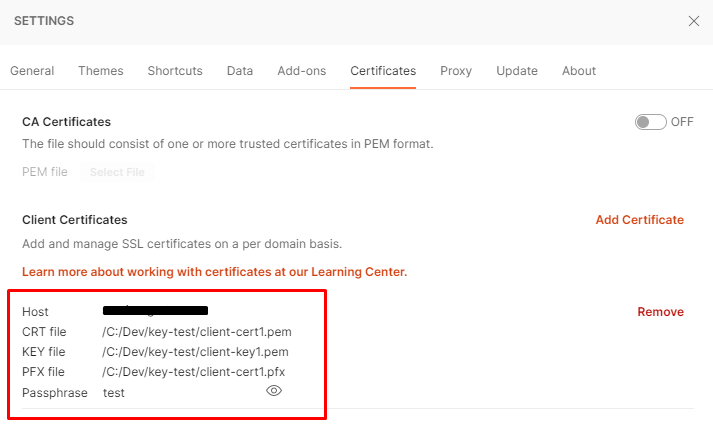

To continue my investigation, I created my own client certificate (signed by myself) following this guide (skipping steps 3 & 4). I added this certificate to Postman using the follow configuration:

I then added the legitimate certificate to the X-ARR-ClientCert header and tried the request again (with part of the JSON body being invalid) and successfully bypassed the server’s mTLS security, receiving a 400 Bad Request response, with detailed information about what was wrong with my JSON body.

This successful response (i.e. not a 403 Forbidden) indicates that the server does not have mTLS properly implemented, allowing anonymous users to make fraudulent requests to its endpoints.

A Note From Future Harrison

I later discovered that I was wrong in a few of places during my investigation:

I wasn’t getting a 400 Bad Request response from the server because I bypassed its mTLS security, but rather because the JSON deserialisation of the body was occuring before the certificate was checked for validitity. This was presumably because the mTLS checks were in the controller endpoint’s method body and not in middleware, like the deserialisation would be.

Whilst you might think that this point calls into doubt my conclusion that the server wasn’t performing mTLS properly, it turns out that it was doing it even worse than I thought (at least, when I re-tested it later it was)! I didn’t need to provide a TLS-level certifcate at all (i.e. the Postman CCA configuration), but only the certificate in the header.

As a result of this, once the mTLS configuration was corrected, I ended up creating an automated testing suite that ensured the mTLS connection with the server was always secure. This required some janky coding and we ended up using .NET hosted services to continuously run the tests in production.

It also turns out that the partner was using AWS, not Azure like I had assumed, and that AWS now provides mTLS support with Amazon API Gateway making it much easier to use mTLS with AWS than it was when we first encountered this issue.

Further reading

How does private key verification happen?

To verify that the server has the corresponding private key to the certificate it provided, the client encrypts the Client Key Exchange (v1.2) message with the server’s public key (provided in the server’s certificate). This means that only a server that has the corresponding private key will be able to decrypt it (this is a function of RSA).

To verify the client has the corresponding private key to the certificate it provided, the client also sends the Certificate Verify message. To create this message the client hashes all previous handshakes messages and then creates a signature over the resulting hash using their private key. The resulting signature can be verified using the client’s public key (provided in the client’s certificate) to verify that the client has the private key corresponding to the provided certificate.

For more information, read up on public-key cryptography and RSA.

Useful Links

A great AspNetCore.Docs GitHub issue discussing exactly the issue we encountered

Certificate Signing Requests (CSRs)

Dissecting TLS using Wireshark

Detailed TLS handshake breakdown using Wireshark (mostly excluding CCA)

mTLSMutual TLSLoad BalancersCCAClient Certificate AuthenticationCryptography

2727 Words

2021-03-28 10:20 +1300